Open search for PTM discovery with FragPipe

The open search strategy allows large mass differences between unmodified peptide sequences and experimentally observed precursors, enabling discovery of post-translational modifications (PTMs) directly from the data without the need to specify them in the analysis. One common use for open searches is finding experimental artifacts that can be included in subsequent closed searches to increase proteome coverage. Many sample preparation methods can modify peptides and reduce the likelihood of recovering them in a typical search. One such protocol is formalin-fixed paraffin-embedding (FFPE), a widely used tissue preservation method. There are a few different modification palettes that have been suggested in the literature (Metz et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2004; Hood et al., Mol. Cell. Proteom., 2005; Zhang et al., Proteomics, 2015) and we are interested in knowing which of these modifications, if any, are most relevant to our data.

For this tutorial, we will use one run (2014-03-14-NSN-38B-2, download from PRIDE) from an FFPE-preserved sample of amyloid deposits in eye tissues, acquired on a SCIEX TripleTOF, originally in .wiff format that needs to be converted to .mzML by ProteoWizard. (Publication: Nielsen, Nadia Sukusu, et al. “Insight into the protein composition of immunoglobulin light chain deposits of eyelid, orbital and conjunctival amyloidosis.” Journal of proteomics & bioinformatics (2014).)

Tutorial contents

- Open FragPipe

- Add the data

- Load the Open workflow

- Fetch a sequence database

- Inspect the search settings

- Set the output location and run

- Examine the results

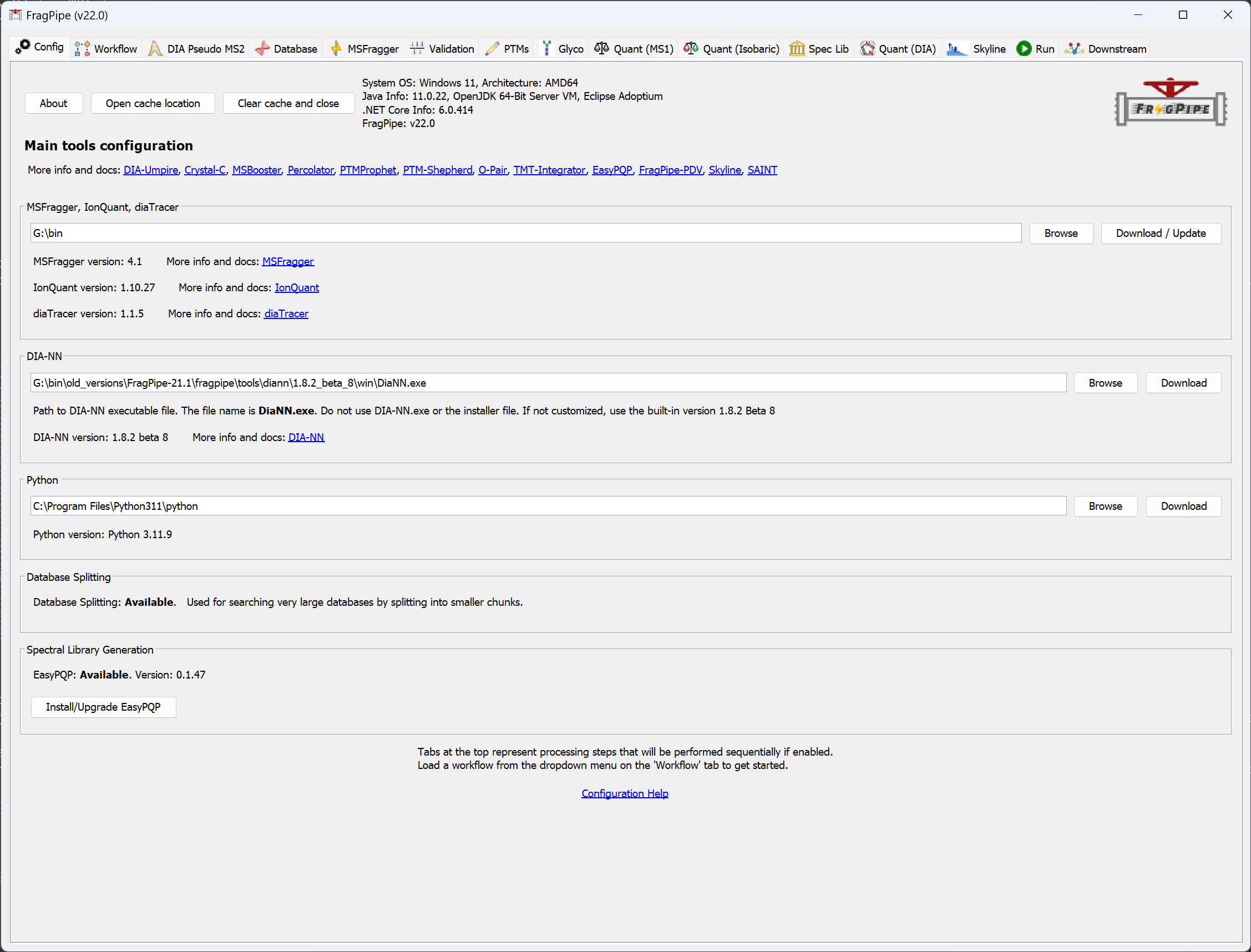

Open FragPipe

When you launch FragPipe, check that MSFragger, IonQuant, and, Philosopher are all configured. If you haven’t downloaded them yet, use their respective ‘Download / Update’ buttons. Please see the tutorials here and here for more help. Python is not needed for this exercise.

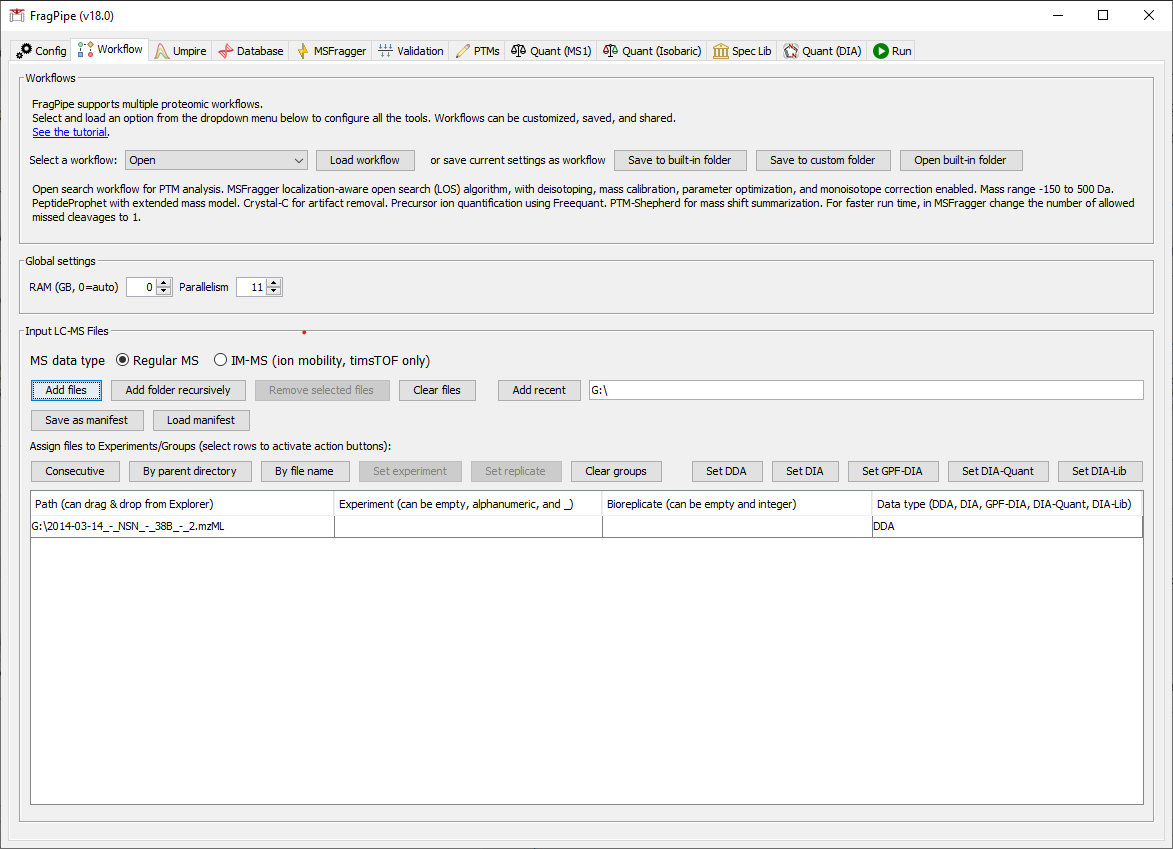

Add the data

- On the Workflow tab, add the

2014-03-14-NSN-36B-2.mzMLfile by dragging and dropping into FragPipe. Since we are only analyzing a single file, we don’t need to provide experiment or replicate labels.

Load the Open workflow

- Fragpipe includes built-in workflows for many common analyses. It is recommended to use the default workflows as a starting point for any custom analyses. Since we will be doing an open search, select the ‘Open’ workflow from the dropdown menu at the top of the page. Click ‘Load’ to configure FragPipe to run a complete open search workflow.

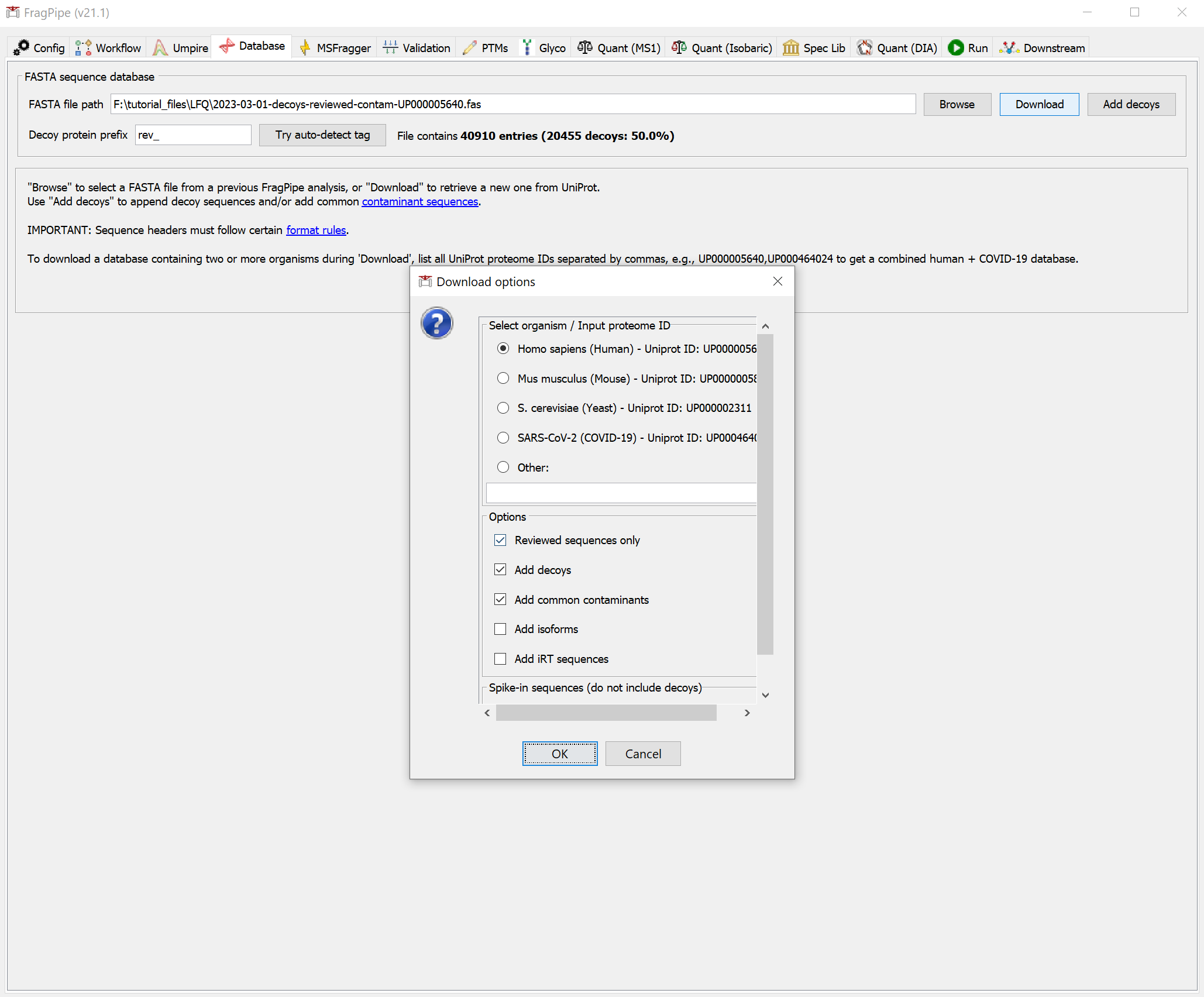

Fetch a sequence database

- Now we need to select a protein sequence database. You can download a human .fas file using FragPipe. Downloading is easy, so we could also choose to download one at this point. On the Database tab, click the ‘Download’ button. Follow the prompts to use the default settings (reviewed human sequences with common contaminants).

Click ‘Yes’ to download the database. When it’s finished, you should see that the FASTA file path now points to the new database.

Inspect the search settings

- On the MSFragger tab, have a look at the search parameters we will use. Note that a wide precursor mass tolerance is set, from -150 Da to +500 Da.

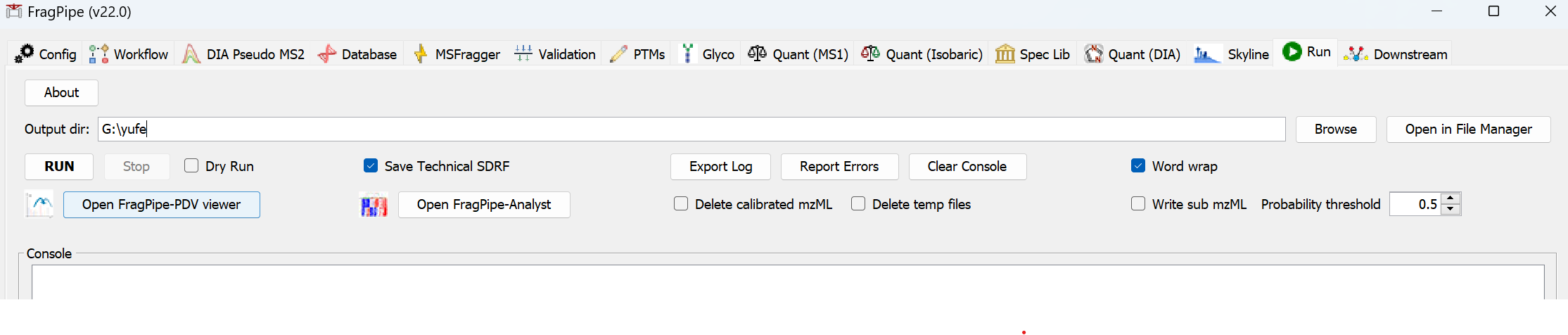

Set the output location and run

- By loading the workflow, all other tabs have already been configured for a basic open search analysis, so skip to the Run tab to set the output location (a new folder called ‘my_FFPE_results’), then click ‘RUN’ and wait for the results.

When the run is finished, ‘DONE’ will be printed at the end of the text in the console.

Examine the results

In the output location (‘my_FFPE_results’ folder), you will find the results of the analysis. A guide to all the output files can be found here.

In the ‘my_FFPE_results’ folder, you will see PTM-Shepherd output files (‘global.profile’ and ‘global.modsummary’) that help interpret all the mass shifts identified from the open search. Open the ‘global.profile.tsv’ file (in Excel or similar) to inspect it. This file summarizes the mass shifts detected from all the FDR-filtered peptide-spectrum matches, sorted from most to least prominent. The contents of each column is described here.

Since we are trying to find PTM artifacts that would increase our proteome coverage by including them in a subsequent search, we need two pieces of information: abundance and localization. As a rule of thumb, it is typically worth including modifications accounting for anything more than 1-2% of the total PSM count in subsequent searches. Here, that cutoff is roughly 30 PSMs, so we will look at the top 6 mass shifts:

- 0.0000: unmodified peptides, 775 PSMs. Unmodified peptides should almost always be included in searches, and some tools expect them to be present.

- 15.9956: oxidation or hydroxylation, 274 PSMs, localized to P. A mass of 16 Da corresponds to a single oxidation event. Because oxidation of M is included as a variable modification in the search, most M oxidation should’t appear as a mass shift. P oxidation was not included as a variable mod, and consequently is showing up at pretty high levels so it should be included in subsequent searches.

- 31.9908: dihydroxy, 105 PSMs, no strong localization. A mass of 32 Da corresponds to two oxidation events. Despite being listed in Unimod as a single modification, this can also be the result a combination of two separate oxidation events on two residues. These two types of modifications can be differentiated from each other by their localization profiles. Mass shifts that are a single modification can generally be localized to their residues of origin. Mass shifts that are a combination of modifications on two separate modifications cannot be localized well because only ions downstream of both modified residues will be shifted by the entire mass shift. The lack of a strong localization profile here indicates that this mass shift is a combination of two separate oxidation events, and as such will probably be captured by the inclusion of a the oxidzed M and P mentioned above.

- 14.0180: methylation, 68 PSMs, strongly localized to K. A mass of 14 Da corresponds to a methylation event. This is straighyforwardly and solely localized to K, and should be included as a variable modification in a subsequent search.

- 196.0460: unannotated mass shift, 46 PSMs, strongly localized to R and moderately localized to E. This mass shift doesn’t appear to have an annotation in Unimod. This might be because it’s actually a combination of modifications (which are more difficult to annotate) or a modification specific to this sample preparation method. One of the benefits of FragPipe is that unknown mass shifts can be easily incorporated without knowing their identities. This mass shift is strongly localized to R and moderately localized to E. When looking at individual residues, this modification only has 15 (R) and 11 (E) PSMs corrsponding to each additional variable mod that would be added if this were included in a subsequent search. It might not be worth it to include these despite the total mass shift passing our threshold because it introduces twice as much computational complexity to the search as a single residue would.

- 28.0340: dimethylation, 36 PSMs, strongly localized to K. A mass of just more than 28 Da corresponds to a di-methylation or ethylation event. Unlike the supposed dihydroxylation event listed above, this modification is clearly and strongly localized to a single residue. The implication is that it is actually a single PTM on a single residue rather than being a combination of two separate PTMs, and as such should be included in subsequent searches.

- *27.9934: formylation, 14 PSMs, no localization profile. *This modification appears to be relatively rare in this dataset but is a useful demonstration of a common occurrence in open searches. A mass shift of just less than 28 Da corresponds to formylation. Notably, this mass shift doesn’t have any localization profile. Aside from being a combination of modifications, as mentioned above, this can have to additional causes: labile modifications and diffuse localizations. Labile modifications can’t be localized well because ions shifted by the mass shift don’t exist in the spectrum. Variable modifications look for shifted ions in the spectrum, so they to a poor job of identifying labile modifications. Labile modifications are better searched for as mass offsets, where peptides are searched for at a shifted mass but shifted ions are not identified (when localization is off). If this modifications were identified at higher abundance, then it might be prudent to search for it as a mass offset (with localization off) rather than as a variable mod. Diffuse modifications–modifications that occur on a wide variety of PTMs–are also best searched for as a mass offset. Unlike variable modifications where each residue that a PTM occurs on should be specified individually, mass offsets can be used to identify PTMs on any residue. If a modification isn’t suspected to be labile but produces no strong localization profile, it may be diffusely targeted and can be comprehensively identified by using a mass offset search (for non-labile modifications, localization is useful).